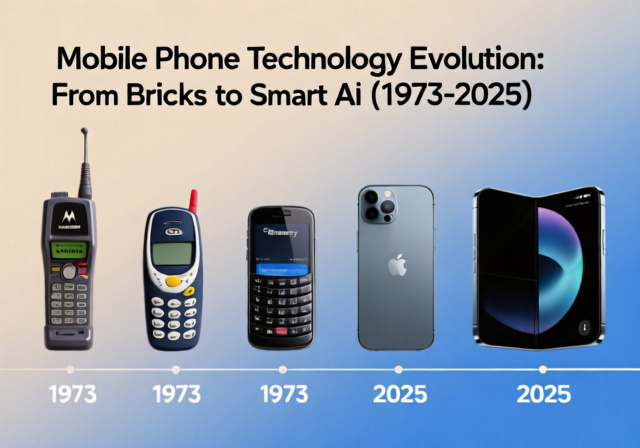

Mobile Phone Technology Evolution: From Bricks to Smart AI (1973-2025)

I still remember the weight of my father’s Motorola DynaTAC in 1989 – a brick-like device that cost him nearly $4,000 and barely fit in his briefcase. Today, I’m writing this on a smartphone that’s 1000 times more powerful than the computers that sent humans to the moon, and it slides effortlessly into my pocket. The transformation of mobile phone technology over the past five decades represents one of humanity’s most remarkable technological achievements.

When I tell my teenage daughter that phones once had cords attached to walls, or that sending a text message used to cost 10 cents, she looks at me like I’m describing life in the Stone Age. Yet this incredible journey from analog voice calls to AI-powered pocket computers happened within a single generation. The mobile phone evolution isn’t just a story of technological advancement – it’s a narrative about how we’ve fundamentally transformed human communication, work, and daily life.

The numbers alone are staggering: from fewer than 1 million mobile phone users worldwide in 1985 to over 7.43 billion smartphone users in 2025. We’ve witnessed the rise and fall of industry giants, the birth of entirely new economies built on mobile apps, and the democratization of information access across the globe. Mobile technology has lifted millions out of poverty, revolutionized banking in developing nations, and connected families separated by oceans.

In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll journey through every major milestone of mobile phone technology evolution – from the first call made on a handheld cellular phone in 1973 to the AI-integrated, 5G-powered devices of 2025. You’ll discover how each breakthrough built upon the last, creating the sophisticated mobile ecosystem we depend on today.

The Birth of Mobile Communication: 1973-1990

The story begins on April 3, 1973, when Motorola engineer Martin Cooper made history’s first mobile phone call from a handheld device on the streets of New York City. I had the privilege of meeting Dr. Cooper at a technology conference in 2018, and his description of that moment still gives me chills. The prototype he used weighed 2.5 pounds, offered 30 minutes of talk time, and took 10 hours to charge. Cooper called his rival at Bell Labs, Joel Engel, marking not just a technological breakthrough but a defining moment in competitive innovation.

The journey from Cooper’s prototype to commercial reality took a full decade. When the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X finally launched in 1983, it carried a price tag of $3,995 (equivalent to over $11,000 today). Despite the astronomical cost, demand was immediate and overwhelming. Wall Street executives, real estate moguls, and Hollywood celebrities embraced these “brick phones” as status symbols. The waiting list stretched for months, and owning one meant you had truly arrived in the business world.

First-generation (1G) cellular networks emerged simultaneously, using analog technology to transmit voice calls. The Advanced Mobile Phone System (AMPS) launched in the United States, while Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) served Scandinavia, and Total Access Communication System (TACS) covered the United Kingdom. These networks operated on different frequencies and standards, making international roaming impossible – a limitation that seems unthinkable today.

The technical challenges of this era were immense. Engineers had to solve problems of signal handoff between cell towers, manage limited spectrum allocation, and create infrastructure from scratch. Each cell tower could handle only a few dozen simultaneous calls, and coverage gaps were massive. Rural areas remained completely disconnected, and even in cities, dropped calls were the norm rather than the exception.

By 1990, mobile phones had shrunk considerably but remained luxury items. The Motorola MicroTAC, introduced in 1989, pioneered the flip phone design and weighed just 12 ounces – revolutionary for its time. I owned one of these in 1991, paying $2,500 and a monthly bill that regularly exceeded $500. The battery lasted about two hours of talk time, and I carried spare batteries everywhere. Text messaging didn’t exist, voicemail was primitive, and the phone served one purpose: making voice calls.

Despite limitations, the foundation was set. By 1990, the United States had 5.3 million cellular subscribers, and the potential for mobile communication was becoming clear. The analog era had proven that people would pay premium prices for the freedom of mobile communication, setting the stage for the digital revolution that would follow.

Digital Revolution and Mass Adoption: The 1990s

The transition from analog to digital networks in the early 1990s marked a fundamental shift in mobile phone technology evolution. Second-generation (2G) networks, primarily using Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) technology, launched in Finland in 1991. I was living in Europe at the time, and witnessing this transformation firsthand was extraordinary. Digital networks offered clearer voice quality, better security through encryption, and most importantly, they introduced a feature that would change everything: Short Message Service (SMS).

The first SMS was sent on December 3, 1992, by engineer Neil Papworth, who typed “Merry Christmas” on a computer and sent it to a mobile phone. Initially, carriers didn’t see the commercial potential – SMS was considered a minor feature for network notifications. By 1995, users were sending an average of only 0.4 messages per month. Nobody predicted that by 2010, we’d be sending 6.1 trillion text messages annually. I remember my first text message in 1994 – pecking out “HELLO” on a numeric keypad using T9 predictive text felt like magic.

Nokia emerged as the dominant force during this decade, transforming from a Finnish paper mill company into the world’s largest mobile phone manufacturer. The Nokia 2110, launched in 1994, became the first mass-market GSM phone, while the iconic Nokia 3210 (1999) sold 160 million units. These phones introduced features we now take for granted: customizable ringtones, vibration alerts, and simple games. Who could forget the addictive nature of Snake, which consumed countless hours of our lives?

Battery technology improved dramatically during the 1990s. The shift from Nickel-Cadmium (NiCd) to Nickel-Metal Hydride (NiMH) and eventually to Lithium-Ion batteries meant phones could last days on a single charge. The Motorola StarTAC, introduced in 1996, weighed just 3.1 ounces and became the first phone to achieve true pocket-ability. I carried one for three years, and it survived countless drops, spills, and even a trip through the washing machine – durability that seems impossible with today’s glass-covered smartphones.

Prepaid mobile services launched in the mid-1990s, democratizing mobile phone access. No longer did users need credit checks or long-term contracts. In developing nations, this model proved revolutionary. Countries like Kenya and India saw explosive growth as prepaid cards made mobile phones accessible to millions who lacked traditional banking relationships. By 1999, mobile phone penetration in Finland reached 65% of the population, the highest in the world.

The decade closed with mobile phones becoming fashion accessories. Interchangeable faceplates, compact designs, and colorful displays turned phones from utilitarian devices into personal expressions. The global mobile phone user base surpassed 490 million by the end of 1999, and the stage was set for the next revolution: the marriage of mobile phones with internet connectivity.

The Dawn of Smart Devices: 2000-2007

The new millennium brought a convergence that would forever change mobile phone technology. I vividly remember the excitement of accessing the internet on my phone for the first time in 2001 – waiting three minutes for a simple weather page to load over GPRS felt revolutionary. Third-generation (3G) networks began rolling out in Japan in 2001, promising mobile internet speeds that could support video calls and web browsing. The reality often fell short of the promise, but the potential was undeniable.

Camera phones emerged as the killer application of the early 2000s. The Sharp J-SH04, released in Japan in 2000, featured a 0.11-megapixel camera that produced grainy, almost unusable images. Yet within five years, camera phones had decimated the digital camera market. By 2003, more camera phones were sold globally than standalone digital cameras. I remember the Sony Ericsson K750i in 2005 – its 2-megapixel camera with autofocus and flash made me retire my digital camera entirely. The ability to instantly capture and share moments transformed how we document our lives.

The BlackBerry revolution began in earnest during this period, transforming mobile email from a luxury to a necessity. The BlackBerry 850, introduced in 1999, evolved into the more sophisticated 5810 in 2002, featuring always-on email synchronization. By 2006, “CrackBerry” had entered the lexicon, describing our growing addiction to constant connectivity. I received my first BlackBerry from my employer in 2004, and suddenly the boundaries between work and personal life began to blur. Email notifications at midnight became normal, and the expectation of immediate response grew exponentially.

Music phones emerged as another battleground. The Nokia 3300 (2003) and Sony Ericsson Walkman phones challenged the iPod’s dominance in portable music. These devices could store hundreds of songs on memory cards, included decent headphones, and eliminated the need to carry multiple devices. The Motorola ROKR E1, launched in 2005 as the first phone with iTunes support, disappointed with its 100-song limit, but it foreshadowed the complete convergence that would soon arrive.

Palm, Windows Mobile, and Symbian competed to define the smartphone operating system. The Palm Treo series combined phone functionality with Palm’s successful personal digital assistant (PDA) platform. Windows Mobile powered devices from HTC and Samsung offered desktop-like experiences with stylus input and Microsoft Office compatibility. Nokia’s Symbian OS dominated globally, powering sophisticated devices like the N95 (2007), which featured GPS navigation, a 5-megapixel camera, and Wi-Fi connectivity.

By 2007, the pieces were in place for a revolution. Mobile phones had evolved from simple communication devices to multipurpose tools incorporating cameras, music players, internet browsers, and email clients. The global mobile phone user base exceeded 3.3 billion, and 3G networks were expanding rapidly. Yet despite these advances, using these devices remained complicated. Most smartphones required styluses, featured cluttered interfaces, and suffered from poor battery life. The stage was set for someone to reimagine the entire mobile experience.

The iPhone and Android Revolution: 2007-2010

On January 9, 2007, Steve Jobs walked onto the Macworld stage and changed everything. “Today, we’re introducing three revolutionary products,” he announced, before revealing they were all one device: the iPhone. I was watching the livestream from my office, and when Jobs demonstrated pinch-to-zoom on the touchscreen, our entire team gasped. The iPhone didn’t just improve on existing smartphones – it completely reimagined what a mobile device could be.

The original iPhone’s specifications seem modest today: 128MB of RAM, a 2-megapixel camera, no app store, and no 3G connectivity. Yet its revolutionary capacitive touchscreen, intuitive interface, and desktop-class web browser made every other phone feel instantly obsolete. I waited in line for six hours to buy one on launch day, June 29, 2007. Using it for the first time felt like handling technology from the future. The smooth scrolling, the responsive touch interface, the way emails and websites looked exactly like they did on a computer – it was transformative.

Google’s response came swiftly with Android, acquired in 2005 but not publicly unveiled until November 2007. The HTC Dream (T-Mobile G1) launched in October 2008 as the first Android phone, featuring a sliding keyboard and deep Google services integration. While initially rough around the edges, Android’s open-source nature attracted manufacturers who couldn’t compete with Apple’s integrated approach. By 2010, Android had captured 23% of the smartphone market, setting up the iOS versus Android rivalry that continues today.

The App Store, launched in July 2008 with just 500 applications, revolutionized software distribution and created an entirely new economy. Within three days, 10 million apps were downloaded. Developers could now reach millions of users directly, and innovations exploded. I downloaded my first apps – Super Monkey Ball, Facebook, and Shazam – and suddenly my phone became infinitely customizable. By 2010, the App Store offered 225,000 apps, and “there’s an app for that” had become Apple’s marketing slogan and a cultural phenomenon.

Social media and smartphones proved a perfect marriage. Twitter, founded in 2006, exploded in popularity as smartphones made real-time, location-based sharing possible. Facebook’s mobile app transformed the platform from a desktop website to an always-accessible social network. Instagram, launched in October 2010 exclusively as a mobile app, gained one million users in two months. The combination of cameras, GPS, and constant connectivity created new forms of human interaction and forever changed how we share our lives.

The period from 2007 to 2010 saw explosive innovation and competition. The iPhone 3G (2008) added 3G connectivity and GPS. The iPhone 3GS (2009) improved speed and camera quality. The iPhone 4 (2010) introduced the Retina display and front-facing camera for video calls. Meanwhile, Android phones proliferated with diverse designs: the Motorola Droid (2009) emphasized keyboards, while the HTC Evo 4G (2010) pioneered large screens and 4G connectivity. BlackBerry peaked with 20% market share in 2009 but failed to adapt to the touch-centric world.

By the end of 2010, the mobile landscape had transformed completely. Smartphones were no longer business tools but mainstream consumer devices. The App Store and Google Play (initially Android Market) had distributed billions of apps. Mobile internet usage was exploding, and companies were scrambling to create mobile-first experiences. We had entered the era where our phones were no longer just communication devices – they were our cameras, music players, gaming devices, navigation systems, and gateways to the world’s information.

The Modern Smartphone Era: 2010-2020

The decade from 2010 to 2020 witnessed smartphones evolving from revolutionary gadgets to essential life tools. Fourth-generation (4G) LTE networks began widespread deployment in 2010, delivering speeds that finally fulfilled the promise of mobile broadband. I remember conducting my first video call over LTE in 2011 – crystal clear, without lag, while walking down a busy street. It felt like living in a science fiction movie. These networks enabled streaming services, cloud computing, and real-time collaboration to flourish on mobile devices.

Screen sizes grew dramatically as phones became our primary computing devices. The Samsung Galaxy Note, launched in 2011 with a 5.3-inch display, was initially mocked as too large. Critics called it a “phablet” – too big for a phone, too small for a tablet. Yet it sold 10 million units in nine months, proving consumers wanted larger screens for content consumption. By 2020, 6.5-inch screens were standard, and we’d adapted our pockets, hands, and habits to accommodate these larger devices. The iPhone 6 Plus (2014) validated this trend when Apple finally embraced larger displays.

Mobile photography underwent a renaissance that destroyed the point-and-shoot camera market. The iPhone 4S (2011) introduced an 8-megapixel camera with impressive low-light performance. The Nokia Lumia 1020 (2013) pushed boundaries with a 41-megapixel sensor. But megapixels became less important than computational photography. The Google Pixel (2016) used machine learning to produce stunning images from a single lens. The iPhone 7 Plus (2016) introduced dual cameras for portrait mode, artificially blurring backgrounds like professional cameras. By 2019, phones featured three or four cameras, ultra-wide lenses, and night modes that could capture detailed photos in near darkness.

Biometric security transformed from gimmick to necessity. The iPhone 5S (2013) mainstreamed fingerprint recognition with Touch ID, making phone unlocking effortless and secure. Samsung experimented with iris scanning and face recognition before Apple’s Face ID (iPhone X, 2017) set new standards for facial authentication. I was skeptical initially, but Face ID’s ability to work in darkness, recognize me with sunglasses, and adapt to facial hair changes won me over. By 2020, biometric authentication had replaced passwords for banking, payments, and sensitive apps.

Processor advancement followed Moore’s Law with stunning consistency. The Apple A4 chip (2010) contained 149 million transistors. The A14 Bionic (2020) packed 11.8 billion transistors, delivering desktop-class performance in a phone. Qualcomm’s Snapdragon processors powered Android devices to similar heights. These chips enabled console-quality gaming, 4K video editing, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence processing directly on the device. My 2020 smartphone benchmarked faster than my 2015 laptop – a reversal that would have seemed impossible a decade earlier.

The decade saw the rise and fall of numerous players. Windows Phone launched in 2010 with innovative live tiles but never gained traction, officially dying in 2017. BlackBerry’s desperate pivot to Android came too late, ending production in 2016. Chinese manufacturers like Xiaomi, Oppo, and OnePlus emerged as serious competitors, offering flagship specifications at mid-range prices. Huawei briefly became the world’s largest smartphone manufacturer in 2020 before U.S. sanctions crippled its ambitions.

5G networks began commercial deployment in 2019, promising speeds up to 100 times faster than 4G, ultra-low latency for real-time applications, and capacity for billions of IoT devices. The iPhone 12 (2020) brought 5G to the mainstream, though the killer applications remained elusive. Battery life became the new battlefield as powerful processors, 5G radios, and high-refresh displays demanded ever more power. Fast charging evolved from luxury to necessity – 65W charging could fill a battery in 30 minutes.

AI, 5G, and Beyond: 2020-2025

The transformation of smartphones into AI-powered assistants represents the current frontier of mobile phone technology evolution. When I compared my 2020 iPhone to my 2024 model, the hardware improvements were incremental, but the intelligence leap was profound. Modern smartphones now predict my needs, understand context, and perform complex tasks that previously required multiple apps and manual input. The integration of large language models directly into mobile operating systems has made our phones feel less like tools and more like intelligent companions.

Apple Intelligence, launched in 2024, and Google’s advanced AI features have redefined user interaction. My phone now summarizes lengthy emails while I commute, transcribes and analyzes meeting recordings in real-time, and even suggests responses that match my writing style. The computational photography has reached near-magical levels – removing unwanted objects from photos, enhancing old images, and creating professional-quality portraits with perfect lighting from casual snapshots. These aren’t cloud-processed tricks; they happen instantly on-device, powered by dedicated neural processing units.

Foldable phones finally matured from expensive experiments to practical devices. The Samsung Galaxy Z Fold5 and Z Flip5 (2023) solved the durability issues that plagued earlier models. The Google Pixel Fold brought stock Android to the foldable space. I’ve been using a foldable as my primary device for six months, and the ability to unfold into a tablet for reading, then fold into a compact phone for portability, feels like the natural evolution of mobile form factors. The crease is barely noticeable, the hinge feels solid after thousands of folds, and the software intelligently adapts to different screen configurations.

5G deployment accelerated globally, with coverage reaching 45% of the world’s population by 2024. The promise of ultra-low latency enabled new applications: cloud gaming services like Xbox Cloud Gaming and NVIDIA GeForce NOW deliver console-quality games to phones without powerful hardware. Remote surgery demonstrations, autonomous vehicle communication, and industrial IoT applications showcase 5G’s potential beyond consumer use. Yet for most users, the difference between 4G and 5G remains subtle – faster downloads, sure, but the transformative applications are still emerging.

Sustainability has become a critical focus as the environmental impact of annual upgrade cycles becomes untenable. Apple’s iPhone 15 series uses 75% recycled rare earth elements. Fairphone continues pushing modular, repairable designs. Samsung committed to using recycled materials in all mobile products by 2025. The European Union’s mandate for USB-C charging (implemented 2024) reduced cable waste, while improved software support – iOS devices now receive six years of updates – extends device lifespans. Consumers increasingly consider environmental impact alongside features when choosing phones.

Privacy and security concerns have reshaped the mobile ecosystem. Apple’s App Tracking Transparency, requiring apps to request permission before tracking users, fundamentally altered mobile advertising. Google’s Privacy Sandbox initiatives attempt to balance user privacy with advertiser needs. End-to-end encryption became standard for messaging apps, while on-device processing for sensitive data reduced cloud dependence. The ongoing tension between convenience and privacy defines much of the current mobile experience, with users increasingly aware of their digital footprints.

The Future of Mobile Technology: 2025 and Beyond

As we stand at the threshold of 2025, the next phase of mobile phone technology evolution promises changes as profound as the shift from feature phones to smartphones. Sixth-generation (6G) networks, targeted for 2030 deployment, promise terabit speeds, sub-millisecond latency, and integration with satellite networks for truly global coverage. The research I’ve seen from Samsung and Nokia suggests 6G will enable holographic communications, brain-computer interfaces, and digital twins of physical spaces accessible through our mobile devices.

Augmented reality glasses are poised to challenge the smartphone’s dominance. Apple’s Vision Pro, while currently a premium mixed-reality headset, hints at lighter, more accessible AR glasses coming soon. Meta’s Ray-Ban smart glasses already offer basic AR features. Within five years, we’ll likely carry phones that project information directly into our field of vision, eliminating screens entirely. Imagine walking through a foreign city with real-time translation floating above street signs, or having repair instructions overlaid on broken appliances. The smartphone might evolve from something we hold to something we wear.

Artificial general intelligence (AGI) integration could transform phones into truly intelligent assistants. Current AI excels at specific tasks, but AGI would understand context, emotion, and nuance like a human assistant. Your phone might proactively manage your schedule, negotiate on your behalf, or create content indistinguishable from human work. The ethical and social implications are staggering – when our phones become smarter than us in many domains, how does that reshape society?

Quantum computing breakthroughs might enable currently impossible mobile applications. While full quantum computers won’t fit in phones soon, quantum-inspired algorithms and cloud-connected quantum processing could solve complex problems instantly. Imagine drug discovery apps that design custom medications, financial apps that perfectly predict market movements, or weather apps providing accurate forecasts weeks in advance. The computational limits that currently constrain mobile applications would essentially disappear.

Brain-computer interfaces represent the ultimate convergence of human and mobile technology. Neuralink and similar companies are developing implants that could connect our thoughts directly to devices. While invasive implants remain years away from mainstream adoption, non-invasive alternatives using advanced sensors to read brain signals might arrive sooner. Controlling phones with thoughts, typing at the speed of thinking, or experiencing full sensory virtual reality through neural stimulation could define the 2030s.

Environmental sustainability will drive radical design changes. Biodegradable components, energy harvesting from movement and solar power, and phones designed for decades of use rather than years might become standard. The concept of “owning” a phone might shift to subscribing to hardware services, with modular components upgraded as needed. The industry’s current model of annual releases and planned obsolescence seems increasingly unsustainable as electronic waste becomes a crisis.

The societal implications of these advances demand careful consideration. We’re already grappling with smartphone addiction, social media’s mental health impacts, and the erosion of privacy. Future technologies will amplify these challenges. How do we maintain human agency when AI assistants make most decisions? How do we preserve privacy when devices can read our thoughts? How do we ensure equitable access to transformative technologies? These questions will shape not just mobile technology but human civilization itself.

From Communication Tool to Digital Life Companion

Reflecting on this incredible journey from the 2.5-pound Motorola DynaTAC to today’s AI-powered supercomputers in our pockets fills me with awe. We’ve witnessed mobile phones evolve from status symbols for the elite to essential tools that billions depend on daily. The transformation happened so gradually yet so quickly that we barely noticed how fundamentally these devices reshaped human existence.

The numbers tell only part of the story. Yes, we’ve gone from 0 to 7.43 billion smartphone users. Yes, processing power increased a millionfold. Yes, costs dropped from $4,000 to devices available for under $50. But the real impact lies in how mobile phones democratized information, connected humanity, and created possibilities our parents couldn’t imagine. A farmer in Kenya can access weather data and market prices. A student in India can attend MIT lectures. A small business in Brazil can reach global customers. These aren’t just technological achievements; they’re human triumphs.

As I write this conclusion, my smartphone sits beside me – a device more powerful than supercomputers from my childhood, connected to virtually all human knowledge, capable of tasks that seemed like magic just years ago. Yet it feels ordinary, even mundane. That normalization of the extraordinary might be mobile technology’s greatest achievement. We’ve integrated these miraculous devices so completely into our lives that we can’t imagine existence without them.

The evolution of mobile phone technology from 1973 to 2025 represents humanity at its best: relentless innovation, creative problem-solving, and the desire to connect and communicate. Whatever comes next – whether AR glasses, brain interfaces, or technologies we haven’t yet imagined – will build upon this foundation. The journey from bricks to smart AI has been remarkable, but I suspect we’re just getting started.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the first mobile phone ever made?

The first handheld mobile phone was the Motorola DynaTAC prototype, demonstrated by Martin Cooper on April 3, 1973. However, the first commercially available mobile phone was the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X, released in 1983 for $3,995. It weighed 2.5 pounds, offered 30 minutes of talk time, and took 10 hours to charge.

How has mobile phone technology evolved from 1G to 5G?

Mobile networks evolved from 1G analog voice-only systems (1980s) to 2G digital networks with SMS (1990s), then 3G with mobile internet (2000s), 4G LTE with broadband speeds (2010s), and now 5G with ultra-fast speeds and low latency (2020s). Each generation brought roughly 10x speed improvements and enabled new applications like video streaming, mobile gaming, and IoT connectivity.

When did smartphones become popular?

Smartphones gained mainstream popularity after the iPhone launch in 2007, though earlier devices like BlackBerry and Palm were popular with business users. By 2011, smartphone sales exceeded feature phone sales globally. The combination of touchscreens, app stores, and improving mobile internet made smartphones essential by 2013, when global smartphone penetration exceeded 20%.

What is the difference between 4G and 5G networks?

5G offers speeds up to 100 times faster than 4G (potentially 10 Gbps vs 100 Mbps), ultra-low latency (1 millisecond vs 50 milliseconds), and can support up to 1 million devices per square kilometer. 5G enables new applications like remote surgery, autonomous vehicles, and immersive AR/VR experiences that weren’t possible with 4G’s limitations.

How did the iPhone change the mobile industry?

The iPhone revolutionized mobile phones by introducing a capacitive touchscreen interface, eliminating physical keyboards, and making the entire front a display. It created the app economy through the App Store, set new standards for mobile internet browsing, and shifted the industry focus from hardware specifications to user experience and ecosystem integration.

What features did early mobile phones have?

Early mobile phones from the 1980s-1990s primarily offered voice calling with basic features like contact storage (usually 10-100 numbers), simple LCD displays showing signal and battery, and later additions like SMS texting, basic games (Snake), customizable ringtones, and vibration alerts. They lacked cameras, internet, apps, or color screens.

When was text messaging invented?

The SMS (Short Message Service) concept was developed in 1984, but the first text message was sent on December 3, 1992, by Neil Papworth who typed ‘Merry Christmas’ on a computer and sent it to a mobile phone. Commercial SMS services launched in 1993, but didn’t gain popularity until the late 1990s when phones made typing easier.

What is the future of mobile technology?

The future includes 6G networks (2030), AR glasses potentially replacing screens, advanced AI integration making phones truly intelligent assistants, brain-computer interfaces for thought control, sustainable designs with decades-long lifespans, and quantum computing capabilities. These advances will transform phones from devices we carry to ambient intelligent systems integrated into our environment.